UN Women supporting female former combatants in the Philippines as agents of peace

Author: Maricel Aguilar

Manila, the Philippines – The Philippines Government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front signed an agreement in 2014 to end the protracted conflict in the Bangsamoro region of the southern Philippines. But while the agreement included provisions on empowering women, women and other groups including indigenous peoples, people living in conflict-affected areas and former combatants are at risk of being pushed to the margins.

With that in mind, UN Women, partnering with the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process, in October 2021 started working with former female combatants and families of another former insurgent group in the region, the Moro National Liberation Front (Misuari Group), to help them build up their women’s organization. The Government’s Final Peace Agreement with the MNLF, signed in 1996, did not contain provisions on women.

Global Affairs Canada, a government department, is funding the initiative, which is part of UN Women’s project, Empowering Women for Sustainable Peace: Preventing Violence and Promoting Social Cohesion in ASEAN. ASEAN is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

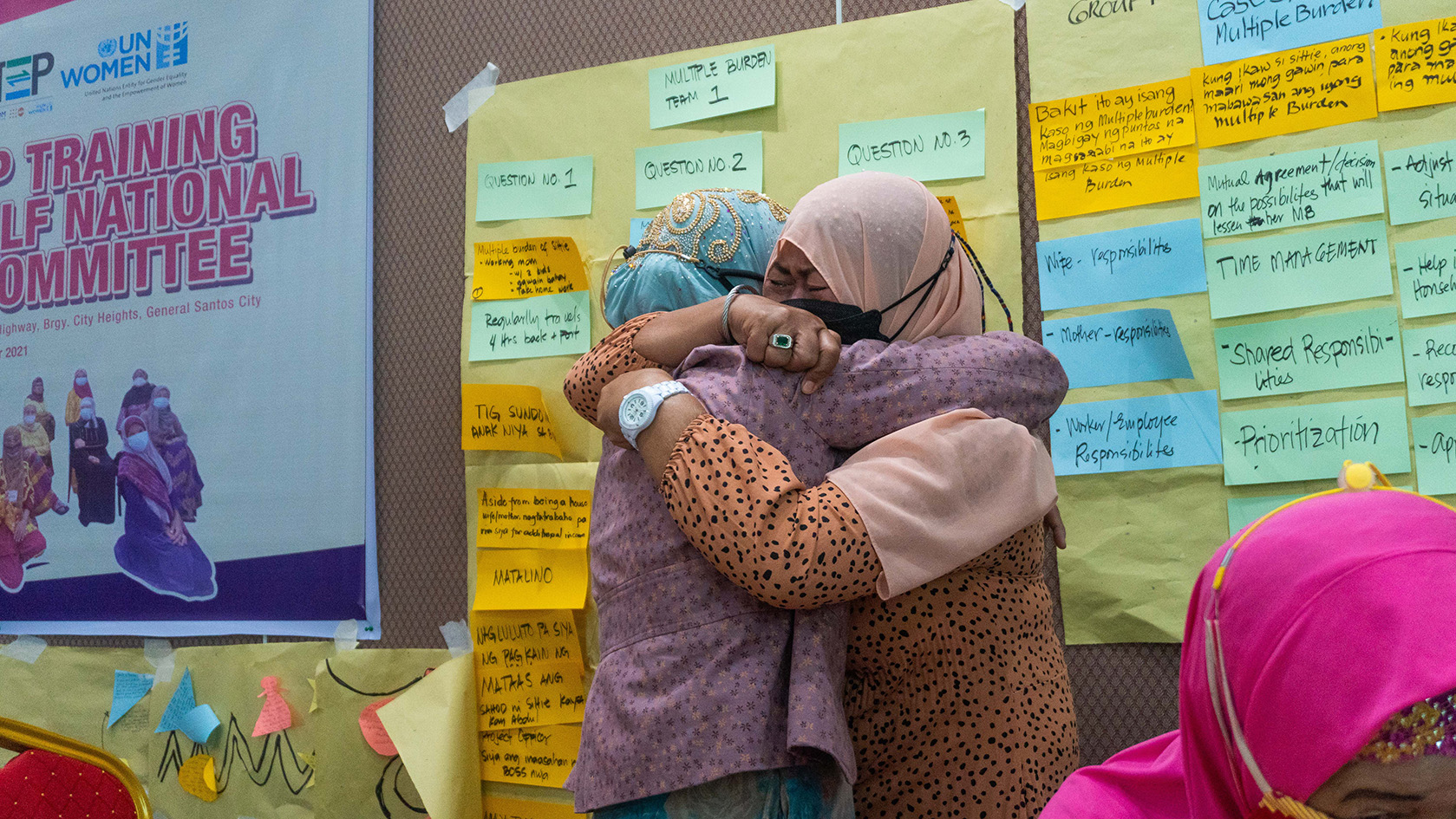

UN Women gave leadership training to 23 members of the MNLF National Women’s Committee during 25-30 October 2021 and plans to give the training to 40 more in May. In coming months, UN Women also plans to support activities to economically empower at least 100 women in the Bangsamoro islands, thus fortifying peacebuilding and humanitarian response.

The leadership training focused on:

- Helping the women understand how their gender is critical to developing leadership

- Reviewing the history of the Bangsamoro from the perspective of the MNLF women and identifying where they could participate more in peacebuilding in their communities

- Strengthening the National Women’s Committee’s vision and goals, including specific activities on women’s empowerment, peace, security and governance

During the training, the MNLF women shared their experiences of leadership in the struggle for self-determination in the Bangsamoro. They led by heading the household while the men were fighting, and by organizing other women and their communities to support the armed struggle. The women also served as food gatherers, medics, message couriers.

The women said there were a lot of losses along the way – lives, property and dignity. With the peace agreement and the establishment of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, these women felt that their losses were worthwhile as they had finally achieved their vision of a new region for the Moro people.

But then the MNLF’s credibility was dented by accusations of corruption and involvement in renewed armed violence, and that affected women’s organizing and leadership in the communities. Some of the women said at the UN Women training that they were further marginalized and impoverished as they were unable to access government programs and services, especially in communities where the military, local governments and the MNLF clashed. Also, differences in ideology and in management of the MNLF resulted in some members falling out and creating their own factions, and the women had to take sides.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the women decided to establish the MNLF National Women’s Committee, which was first set up in the early 1970s, as a formal organization. They want to build an organization based on values and a successor leadership of younger people who will pursue the committee’s vision, mission and goals.

“We recognize that some of our elders, our mothers and aunties, are already in their twilight years. We need to learn from their experience but adapt them to current realities,” said Ainee Lim, focal person of the women’s committee.

At the UN Women training, the women said that for their goals to be achieved, the MNLF must rebuild its relationships with local governments and communities – with women playing a crucial role in rebuilding trust.

“The women resonated with the concept of transitional justice, which is a crucial pillar in peacebuilding,” said Jana Gallardo, the director of the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process.

“They wanted also to be heard as women in the armed struggle, writing their own narrative of the conflicts they have been involved with and sharing it with the next generation so that they understand what they fought for.”